There were 24 children in the room when the policeman began firing

During a trip to Kosovo I return on a whim to the scene of a brutal massacre I wrote about 23 years ago and find unexpected warmth, generosity and dignity in a man who lost everything.

PART 1/2

Just over a week ago I had one of the most unexpected and poignant reunions I have had in a long time. I was in central Kosovo with Emma, my daughter, Leman, my old wartime translator, and a film crew.

We were there to make a documentary about a little boy called Besnik who had survived a massacre I had written about during the 1998-1999 conflict between the Kosovo Albanians and the Serbs.

On a whim I decided to visit the site of another massacre I had also written about, this one in a village called Poklek.

When we arrived in the village the locals pointed us to a man who still looked after the house where the crime had been committed.

He had kept the room where the victims died as it was, but installed a plexiglass screen to stop visitors who came from treading on bone fragments that were mixed in with ashes on the floor.

As I stood at the threshold to the room, I was surprised to feel something begin to well up inside me. It was if a dormant memory of something long-repressed was stirring.

I leaned against the wall to steady myself. When the man offered to show me another room where he had hung photographs of the victims I refused.

"I am sorry," I said.

*

A little later we headed to a café in a nearby town to drink coffee. As I talked to the man I suddenly had a flicker of remembering. It was as if we had met before.

I thought about a photograph of some of the children killed in the massacre. For some reason long after the details of the killing had faded from my memory the photograph had stayed with me.

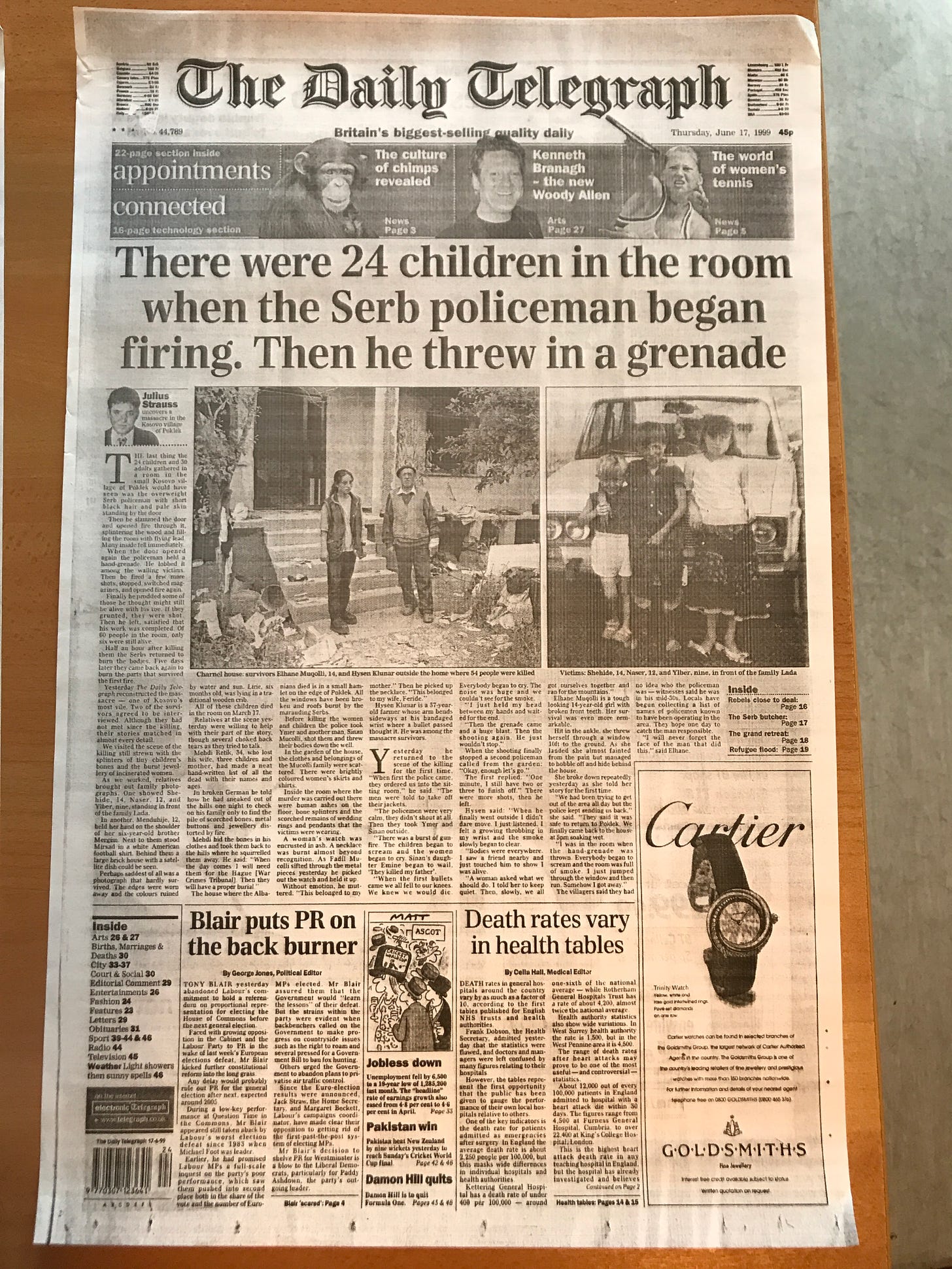

It showed three children, Shehide, aged 14, Naser, 12, and Ylber, nine, sometime before the war had begun, standing shyly in front of the family's white Lada car. Naser has his arm around Ylber.

The children’s father had shown me the photograph on the day I found the massacre and it had run in the Daily Telegraph next to my description of the event.

Now I described the photograph to the man I was talking to. For just a second he hesitated.

Then he said: "Those children were mine."

I was uncertain. Perhaps something had been lost in translation, or there was some confusion.

I searched though the archives on my phone for the story I had written about the massacre and scanned the names of the people I had interviewed.

They included two survivors and a number of family members who had not been present but had returned later.

I read them out slowly: Elhame Mucolli, Hysen Klunar, Fadil Mucolli….

"I am Fadil Mucolli," he said.

"Then you must have been…." I began.

"I was the man who showed you that photograph," he said.

*

It was two months after the killing that I had driven with video journalist Vaughan Smith, now the owner of the Frontline Club in London, deep into central Kosovo behind Serb lines just as the war was ending.

As we arrived in the Poklek area two locals waved us down. "There's been a massacre," one of them said.

Fadil had been at the scene. He showed us the massacre site and we sifted through the charred human remains.

At one point he picked out a burned pocket watch and held it up.

"This belonged to my father," he said, without emotion.

Then he picked up a necklace encrusted with ashes.

"This belonged to my wife, Feride."

Later I asked if there were pictures of the children that had died. And that was when he had produced the battered old photograph that had made such an impression on me.

*

The next day an account of the killing that I had pieced together appeared on the front page of the Telegraph, next to two photographs - one of the children with the Lada, and the other of two of the survivors.

One of the last things the 24 children and 30 adults crammed into a small room in central Kosovo would have seen was the overweight Serb policeman with short black hair and pale skin standing by the door.

Then the policeman slammed the door closed and opened fire through it with an assault rifle, splintering the wood and filling the room with flying lead.

When the door opened again, the policeman was holding a hand grenade. He lobbed it into the room. Then he fired a few more shots, stopped, slipped a fresh magazine into his gun, and opened fire again.

Finally, he prodded some of those he thought might still be alive with his boot. If they showed signs of life, he shot them. Then he left, satisfied that his work was complete. He had killed 54 of the 60 people who were in the room.

Half an hour after the massacre, the Serb policeman returned with colleagues to burn the bodies. Five days later, they came back again to burn the parts that survived the first fire.

Hysen Klunar, a 57-year-old farmer whose arm was bent sideways at his bandaged wrist where a bullet passed through it, had been one of the six in the room to have survived the massacre.

"The policeman was very calm, " he said. "When the first bullets came, we all fell to our knees. Everybody began to cry. The noise was huge and we couldn't see for the smoke."

"I just held my head between my hands and waited for the end. Then the grenade came and a huge blast."

When the shooting finally ended, Hysen said, a second policeman called from the garden: "Okay, enough, let's go."

The killer replied: "One minute, I still have two or three to finish off." There were more shots, then he left.

*

This is Part One of this post. In Part Two Fadil and I discuss loss, grief and the joy we found in our unexpected reunion. I will also talk about the status of the documentary Emma and I are making, and give some details of upcoming plans.

Thank you so much for writing this and interviewing the poor father that lost his children. Our history has been erased by Serbs and they still hide the genocide. I truly am very thankful for sharing our story with the world 🙏

Just another heartbreak in the annals of man's inhumanity toward man. But thank you for sharing these experiences with us as it is very important for the world to not forget what man is capable of perpetrating.